Ninja Build for Asset Baking

Sun 22 January 2023

Michael Labbe

#code

Ninja Build is typically used as a low-level source builder for CMake, Meson or GENie, but it is incredibly good at building game asset files, too.

Frogtoss Tech 3, the current-gen Frogtoss engine, uses Ninja to bake all assets (lighting, texture compression, etc). This has proven to be an extremely reliable and high performing choice. In terms of effort-for-results, it was a clear win for me.

Ninja tracks which files need updating on re-run, builds a DAG and executes all of the commands using your available cores. It supports incremental builds with great reliability and can be integrated to bake a source asset tree in a matter of hours from the start of experimentation.

The rest of this article makes the case for exploring using Ninja for baking assets.

Many developers have used Ninja to build source through CMake, or otherwise. It’s billed by the official website as supporting the low-level parts of building:

Where other build systems are high-level languages Ninja aims to be an assembler.

Many high level tools with incredible flexibility such as Meson generate Ninja files. Once Meson, GENie or CMake does this initial project scan, the Ninja file is generated and the project can be efficiently rebuilt.

Today, I am inviting you to look at Ninja quite differently than how it is advertised. In my view, Ninja is good for two things that aren’t frequently mentioned:

-

Ninja files are straightforward to write by hand. Sure, you wouldn’t want to do it all the time, but you can learn it quite quickly.

-

Ninja’s executable is easily distributable to your co-developers. It’s a much smaller dependency than Make/Bash to inflict on your Windows developers — just a single 600kB executable per platform.

For these reasons, I use Ninja even when its performance benefits are not necessary.

The official manual on writing your own ninja files is fairly short, but if you’re building assets and not source, you can cherry pick three things to get started:

- How to write rules

- How build statements work

- (optional) How variables work

Hand-writing your first experimental Ninja build file that can build a few of your assets is an exercise that should take less than half an hour.

From there, it is pretty clear to see how one could write a script to walk their asset tree and create a ninja build file. Many source asset trees are built from convention: a certain extension in a certain directory tells you everything you need to know to produce the output asset for a specific platform.

If you write your own Ninja Build generator that consists of rules and statements, I would encourage you to not be constrained by languages that include libraries that help you build Ninja files. In my case, this was achieved in about 200 lines of Rust with no third party crates.

Clangd With Unity Builds

Sat 14 January 2023

Michael Labbe

#code

So, you’re programming in C/C++ and your editor is live-checking your code, throwing up errors as you type them. Depending on your editor you’re either getting red underlines or some sort of marker in the margins that compels you to change it. But how does this source code processing engine work, and what can you do when things go off the rails when you attempt something like a unity build?

You may have configured your editor to use a language server called clangd, or it may have been configured for you.

Clangd also offers other benefits, such as go-to-definition and code completion. It runs as a subprocess of your editor, and that means it’s doing its indexing work off the main thread as you would hope.

Clangd can be configured to work with VSCode and Emacs amongst others.

Problem 1: Clangd doesn’t understand how you build

You’re coding along and need to include a bunch of files from a library, so you add a new include path to your build with -Isome_lib/. Unfortunately, clangd doesn’t nkow that you build with this, so a bunch of ugly, incorrect compile errors pop up in your editor.

If you employ your Google-fu, you land on a page that says that Clangd lets you specify your compile flags in a yaml file called .clangd. But, wait! There is a better way. You really want to automate this, or you’ll have to maintain two sets of all your compile flags, which sounds like one of the least enjoyable things you could possibly fritter your time away on.

The good news is that Clangd, alternatively, reads in a compile database, which is just a JSON-structured list of the commands needed to compile each file in a given way. There are plenty of tools that can generate a compile database automatically. For example, if you can output Ninja Build files, you are one step away:

ninja -t compdb > compile_database.jsonClangd recursively searches up the tree to find this file, and uses it to try and compile your files. If a source file exists in your codebase but isn’t in the compile database, it will infer the flags needed to compile it from other commands in adjacent files in this directory. This is most likely what you want, and it’s a great starting point.

You should run this command as a post-build step, or after updating your source repo in order to automatically update your compile database so you never have to worry about keeping your compile flags in sync again.

Problem 2: Clangd adds annoying warnings you don’t want

Sometimes your on-the-fly error checking is too quick on the draw. It tells you about warnings you’d rather only see when you’re compiling. Warning about unused functions is one such example — you declare a function as static and intend to call it. But, before you have a chance to call it, it throws a distracting error. Let me finish typing, Clangd!

One option is to use a compile database post processor that ingests the Clang database that is spat out from Ninja, letting you make the tweaks you need. Now you have automation and customization.

I wrote a compile database post processor that you pipe your output through. Now your command looks like:

ninja -t compdb | \ cleanup-compdb > compile_commands.jsonLet’s say you want to disable the warning for unused functions. cleanup-compdb can append a flag for that to each compile command:

ninja -t compdb | \ cleanup-compdb \ --append-arguments="-Wno-unused-function" \ > compile_commands.jsonProblem 3: Clangd doesn’t understand unity builds

Let’s start by defining the problem.

You have a c “root” file that #includes one or more “sub” files which produce a single translation unit. Clangd now deftly handles the root file and locates the includes. However, Clangd has no concept of c source that is not a stand alone translation unit, so the sub files generate more benign errors than you can count.

Clangd doesn’t have support for unity builds. However, we can instruct it to resolve the necessary symbols as if the sub files were each their own translation unit for error checking purposes.

To illustrate this technique let’s define the root translation unit as root.c, and the sub units as sub0.c, sub1.c, and so on.

An additional file root.unity.h will be created that has all of the common symbols for the translation unit.

The steps to factoring your Unity build for Clangd

-

Create a

root.unity.hfile that starts with#pragma onceand includes all common symbols in the translation unit, including system headers and forward declarations. -

Create

root.cwhich includesroot.unity.hbefore anything else. Doing anything else in this file is entirely optional. -

Create

sub0.cand start it off with#pragma onceand then includeroot.unity.h. -

Include

sub0.cat the bottom ofroot.unity.h. -

Repeat steps 3 and 4 for any other sub-files in the unity build.

This has the following results:

- For real compilations,

root.ccompiles and includessub0.cand ignores the second include ofroot.unity.hthat comes fromsub0.cbecause that file starts with#pragma once. - For Clangd processing of

root.c, the previously described compilation works similarly and everything just works. - For Clangd processing of

sub0.cas the faux-main translation unit, it includesroot.unity.hand all symbols resolve, thus fixing the litany of errors.

One hiccup remains. Clangd now emits this warning:

warning: #pragma once in main fileThis is but a hiccup for us if we are using a compilation database postprocessor as described in problem 2. Simply append -Wno-pragma-once-outside-header to the list of warnings we want to ignore.

Conclusion

Jumping to symbols in an IDE and getting accurate compilation previews is a problem that has been imperfectly solved for decades, even with commercial plugins in Visual Studio. This blog post proposes a few tweaks to the language server Clangd which, in exchange for paying an up-front effort cost, automates the maintenance of a compilation database that can be tweaked to suit your specific needs.

In taking the steps described in this blog post, you will gain the knowhow to adapt the existing tools to a wide range of C/C++ codebases.

I propose a new technique for unity builds in Clangd that operates without the inclusion of any additional compiler flags. If you are able to factor your unity builds to match this format, it is worth an attempt.

Low Overhead Structured Logging in C

Mon 27 December 2021

Michael Labbe

#code

Sure, we call it printf debugging, but as projects get more complex, we aren’t literally calling printf. As our software is adopted we progress to troubleshooting user’s logs. If we’re granted enough success we are faced with statistically quantifying occurrences from many users logs via telemetry.

This is best served by structured logging. There are many formal definitions of structured logs, but for our purposes a simple example will do. Say you have this log line:

Player disconnected. Player count: 12A structured log breaks fields out to make further processing and filtering trivial. This example uses JSON but it can be anything consistent that a machine can process:

{ "file": "src/network.c", "line": 1000, "timestamp": "1640625081", "msg": "Player disconnected.", "player_count": 12}The structured version looks like a message that can be processed and graphed by a telemetry system, or easily searched and filtered in a logging tool.

Coming from backend development where structured logging is expected and common, I wanted this function in my next game client. Because client performance is finite, I sought a way to assemble these messages using the preprocessor.

In practice, a fully structured message can be logged in one single function call without unnecessary heap allocation, unnecessary format specifier processing or runtime string concatenation. Much of the overhead in traditional loggers can be entirely avoided by building the logic using the C preprocessor.

The rest of this post illustrates how you might write your own structured logger using the C preprocessor to avoid runtime overhead. Each step takes the concept further than the one before it, building on the previous implementation and concepts.

Rather than supply a one-size-fits-all library, I suggest you roll your own logger. Stop when the functionality is adequate for your situation. Change the functionality where it does not fit your needs.

Step Zero: printf()

The most basic logger just calls printf(). For modest projects, you’re done! Just remember to clean up your logs before you ship.

Step One: Wrap Printf()

It is useful to wrap printf() in a variadic macro, which can be toggled off and on to reduce spam and gain performance on a per-compilation unit basis.

As of C99, we have variadic macros. The following compiles on Visual C++ 2019, clang and gcc with --std=gnu99.

#define LOGF(fmt, ...) fprintf(stdout, fmt, __VA_ARGS__);#define LOG(comment) puts(comment);Why do we need a special case LOG() that is separate from LOGF()? Unfortunately, having zero variadic arguments is not C99 compliant and, in practice, generates warnings. For conciseness, the rest of this post only provides examples for LOGF(). However, a full implementation would handle both the zero argument and the non-zero argument cases wholly.

Step Two: Route Logs

Having logs print to stdout, also append to disk or submit to a telemetry ingestor are all useful scenarios. Changing where logs are emitted can be reduced to a series of preprocessor config flags.

// config#define LOG_USE_STDIO 1#define LOG_USE_FILE 1// implementation#if LOG_USE_STDIO# define LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF(stream, fmt, ...) \ fprintf(stream, fmt, __VA_ARGS__);#else# define LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF(stream, fmt, ...)#endif#if LOG_USE_FILE# define LOG__FILE(stream, fmt, ...) \ fprintf(stream, fmt, __VA_ARGS__); \ fflush(stream);#else# define LOG__FILE(stream, fmt, ...)#endifNote the call to fflush() ensures the stream is correctly written to disk in the result of an unscheduled process termination. This can be essential for troubleshooting the source of the crash!

Now we have two macros LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF() and LOG__FILE() which either log to the respective targets or do nothing, depending on configuration. The double underscore indicates the macro is internal, and not part of the logging API. Replace the previous LOGF() definition with the following:

#define LOGF(fmt, ...) \{ \ LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF(stdout, fmt, __VA_ARGS__); \ LOG__FILE(handle, fmt, __VA_ARGS__); \}Opening handle prior to calling LOGF() is an exercise left up to the implementer.

Step Three: Log Levels

Limiting logging to higher severity messages is useful for reducing spam. Traditional logging packages call into a variadic function, expending resources before determining the log level does not permit the log line to be written.

We can do better — our logging system simply generates no code at all if the log level is too low.

#define LOG_LEVEL_TRACE 0#define LOG_LEVEL_WARN 1#define LOG_LEVEL_ERROR 2#if !defined(LOG_LEVEL)# define LOG_LEVEL LOG_LEVEL_TRACE#endifThe test for LOG_LEVEL being pre-defined allows a user to control the log level on a per-compilation unit basis before including the logging header file. This is extremely useful for getting detailed logs for only the section of code you are currently working on.

With this in mind, delete the LOGF definition, and replace it with the following:

#define LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF(T, fmt, ...) \{ \ LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF(stdout, T ": " fmt, __VA_ARGS__); \ LOG__FILE(handle, T ": " fmt, __VA_ARGS__); \}#if LOG_LEVEL == LOG_LEVEL_TRACE# define LOG_TRACEF(fmt, ...) LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF("TRC", fmt, __VA_ARGS__);#else# define LOG_TRACEF(fmt, ...)#endif#if LOG_LEVEL <= LOG_LEVEL_WARN# define LOG_WARNF(fmt, ...) LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF("WRN", fmt, __VA_ARGS__);#else# define LOG_WARNF(fmt, ...)#endif#if LOG_LEVEL <= LOG_LEVEL_ERROR# define LOG_ERRORF(fmt, ...) LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF("ERR", fmt, __VA_ARGS__);#else# define LOG_ERRORF(fmt, ...)#endifAdding or changing log levels is an exercise left up to the user. Do what works for you.

Note the obscure T ": " fmt syntax. Rather than pay the overhead of invoking snprintf(), or allocating heap memory to prefix the log line with “TRC”, “WRN” or “ERR”, we use preprocessor concatenation to generate a single format string at compile time.

At this point, you should be able to write the following code:

#define LOG_LEVEL 0#include "log.h"LOG_TRACEF("Hello, %d worlds!", 42);and see the log line

TRC: Hello, 42 worlds!on stdout, and in your log file.

Step Four: Structuring the Logs

C gives us macros for the file and line each log line was generated on. Before we go on to support specific structured fields, we can already generate a structured log with four fields:

- The log level

- The file the log message originated from

- The line of code the log message originated from

- The formatted message itself.

At the beginning of this post a JSON-structured log was used as an example of a structured log. However, there is a runtime cost to escaping logged strings in order to produce valid JSON in all cases that we would like to avoid. Consider:

LOG_TRACE("I said \"don't do it\"");Unless processed, this would produce the ill-formatted JSON string

"I said "don't do it""Structured Log Message Specification

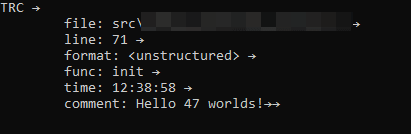

Rather than generate structured JSON, another logging format is used, which can be postprocessed into JSON with a small script if necessary.

- A logging message starts with the 3-byte logging level and a newline. Eg: “TRC” or “WRN”, followed by a newline.

- Each subsequent field’s key is a tab following by alphanumeric characters, a colon and a single space character.

/^\t[a-zA-Z0-9]+:\x20/

- Immediately following, the structured field’s value is every byte until the three byte end-of-line sequence

0x200x1A0x0Ais encountered./.+\x20\x1A\n/

- Further fields follow until the final field, which is terminated with the two-byte sequence

0x1A0x1A./\x1A\x1A$/.

- Note that the final field does not also contain the three byte end-of-line sequence.

This results in a structured log message which is machine-parsable, but is also human readable on popular Linux UTF-8 terminals, as well as DOS codepage 437 (the DOS Latin US codepage). Unless your log messages contain the highly obscure byte sequences described above (unlikely!), we do not need to do any runtime escaping, even for newlines.

Structured Log Implementation

A structured log is one long string that is concatenated in the preprocessor. Here we provide a mechanism to let the user choose between flat and structured with a preprocessor flag.

// config#define LOG_USE_STRUCTURED 1// implementation#define LOG__EOL "\x20\x1A\n"#define LOG__EOM "\x1A\x1A\n"#define LOG__FLAT(file, line, level, msg) \ level " " file ":" line " |" msg "\n"#define LOG__STRUCTURED(file, line, level, msg) \ level LOG__EOL \ "\tfile: " file LOG__EOL \ "\tline: " line LOG__EOL \ "\tmsg: " msg LOG__EOM "\n"#if LOG_USE_STRUCTURED# define LOG__LINE(file, line, level, msg) \ LOG__STRUCTURED(file, line, level, msg)#else# define LOG__LINE(file, line, level, msg) \ LOG__FLAT(file, line, level, msg)#endifNow a call to LOG__LINE() generates either a flat or structured string which can be passed into a printf-style format specifier parameter. We redefine LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF() as follows:

#define LOG__XSTR(x) #x#define LOG__STR(x) LOG__XSTR(x)#define LOG__DECL_LOGLEVELF(T, fmt, ...) \{ \ LOG__STDIO_FPRINTF(stdout, \ LOG__LINE(__FILE__, LOG__STR(__LINE__), #T, fmt), \ __VA_ARGS__); \ \ LOG__FILE(handle, \ LOG__LINE(__FILE__, LOG__STR(__LINE__), #T, fmt), \ __VA_ARGS__); \}Note the use of LOG__STR(__LINE__) is necessary to stringify __LINE__, which is an integral constant. Because we concatenate it at compile time, it must be stringified.

Step Five: Structured Logging With Custom Fields

Structured logging of custom fields pushes the boundaries of what can be done by C preprocessing. Internally, we run a precompile step that:

- Defines C-style structs in a custom language

- Generates a C header file with those structs

- Generates a C macro that logs each field of the struct in a structured manner

- Defines visualizations for it in our telemetry visualization software

Building such a script and hooking it up as a precompile step is out of scope for this post. However, it is possible to perform this work incurring a single snprintf() at runtime.

Putting It All Together

Despite all of these changes and improvements, a logging call to print to stdout will still result in a single function call. To test that, we view the preprocessed output of a LOG_TRACEF() call generated with clang -E:

// logging call in sourceLOG_TRACEF("Hello %d", 42);// output of clang's c preprocessor (newlines added){ fprintf(stdout, "\"TRC\"" "\x20\x1A\n" "\tfile: " "main.c" "\x20\x1A\n" "\tline: " "10" "\x20\x1A\n" "\tmsg: " "Hello %d\n" "\x1A\x1A\n" "\n", 42);; ; };;Success — we can see only one call being made and it’s to the library function fprintf to log the message. On Windows console it looks something like this:

The little arrows are the end-of-line and end-of-message markers, essential for further machine processing.

Processing Structured Logs

As explained, further processing of logs into JSON may be a necessary step before telemetry ingestion. This Python script accepts structured logs streamed from stdin. It outputs properly formatted JSON.

Sample Code

Here is sample code assembled from the snippets in this post.

License

All of the sample code in this blog post and in the linked gist are Copyright © 2021 Frogtoss Games, Inc., and are free to use and modify under the terms of the MIT license.